Economic growth depends on population expansion and the formation of new households. While the idea of fewer people—less congestion, smaller crowds, and reduced strain on infrastructure—may seem appealing, the risks associated with population decline are often understated. Much like deflation, a shrinking population poses serious and potentially greater threats to long-term economic stability.

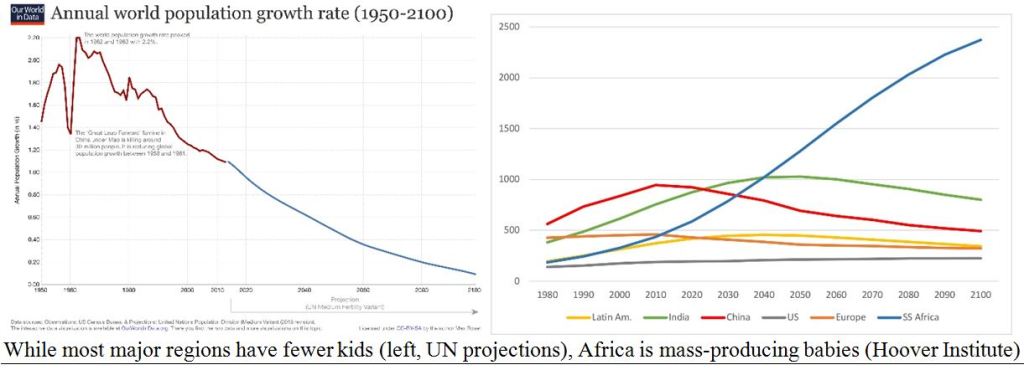

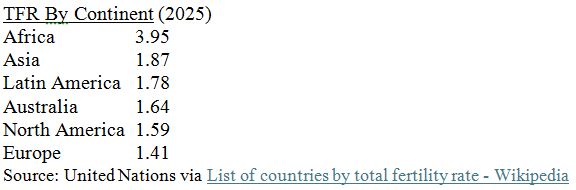

Demographers use the “total fertility rate” (TFR), defined as the average number of births per woman, as a key measure of population sustainability. A TFR of at least 2.1 is required to maintain a stable population, with the additional 0.1 accounting largely for infant mortality. Although the global TFR stood at 2.24 last year, this figure masks significant regional disparities. Excluding Africa, the global fertility rate falls well below 2.0.

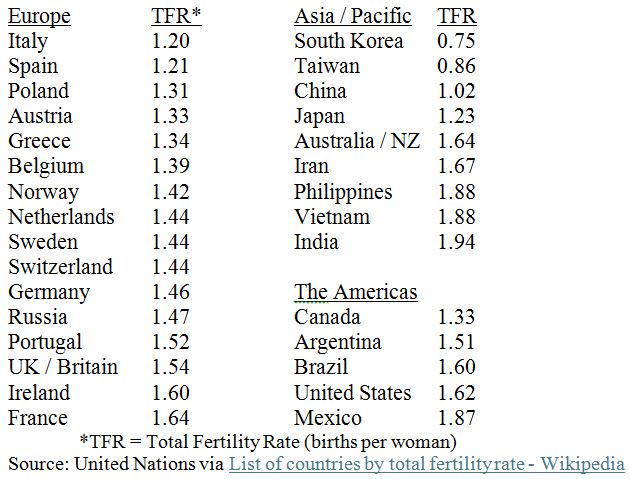

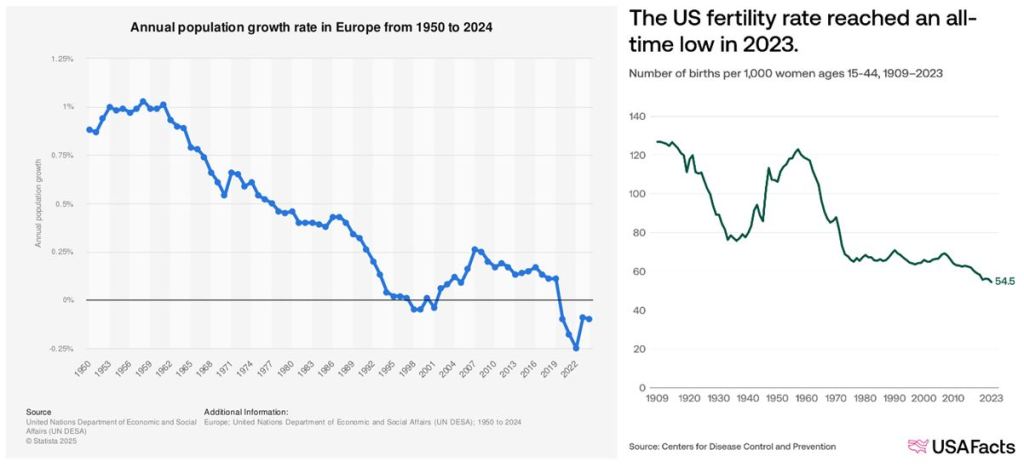

In 2025, most major advanced economies reported TFRs under the replacement threshold of 2.0, underscoring the growing demographic challenge facing industrialized nations.

No major developed economy currently records a total fertility rate above the 2.1 replacement threshold. Outside of Africa, global population growth is already in decline. Historically, from 1950 to 1970, the world’s wealthiest nations averaged more than 2.7 births per woman. Since 1995, however, that figure has fallen sharply to around 1.6, reaching a record low of approximately 1.5 during the 2020–2025 period.

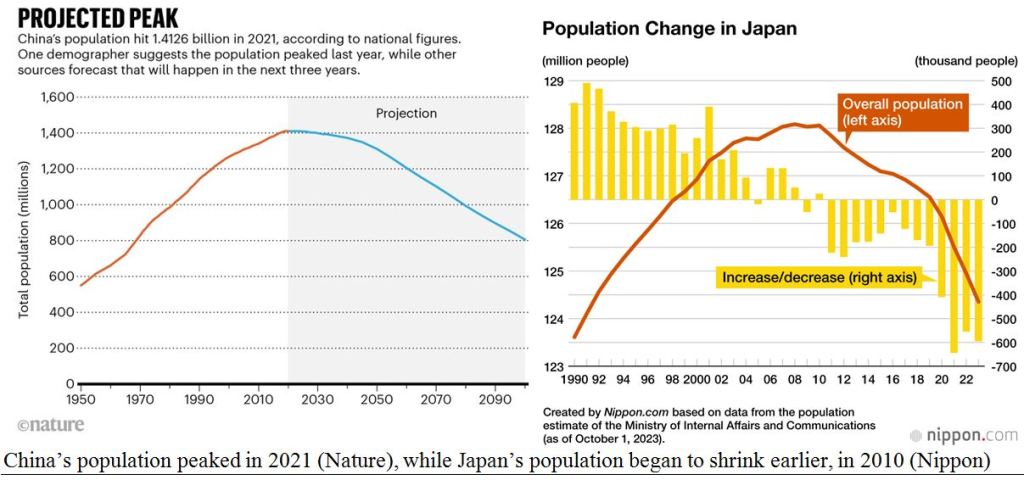

Globally, population growth remains marginally positive, driven largely by demographic expansion in Africa and rising life expectancy among older populations. However, Asia’s two largest economies—China and Japan—are experiencing population decline, a trend that constrains their long-term growth potential. More critically, shrinking cohorts of younger workers are increasingly unable to shoulder the financial burden of supporting aging populations that are living longer and often facing higher healthcare needs.

China has formally abandoned its long-standing one-child policy, but behavioral patterns shaped by decades of enforcement have proven difficult to reverse. Today, many young couples are reluctant to have even a single child, prioritizing career advancement and higher incomes instead. Compounding the challenge, the legacy of the policy produced severe demographic distortions. Prior to 2010, widespread prenatal sex selection—driven by the desire to raise a single male “heir” to support parents in old age—led to a significant gender imbalance, with roughly 118 male births for every 100 female births between 2002 and 2008. The result is a surplus of men and a shrinking pool of potential spouses.

In the mid-1990s, a typical Chinese household consisted of four grandparents, two parents, and one heavily relied-upon child—the so-called “young emperor.” This inverted demographic pyramid is financially unsustainable, as the burden of supporting multiple generations increasingly falls on a single income earner.

Europe faces an even steeper demographic challenge. With an average fertility rate of just 1.4 children per woman and a comparatively generous system of old-age pensions, the region confronts mounting fiscal pressure. These constraints help explain Europe’s historical reliance on the United States for security spending—a strategy that may prove risky as President Donald Trump presses European nations to assume greater responsibility for their own defense.

The United States remains in a stronger demographic position than Europe or much of Asia, in part because of its relatively effective assimilation of immigrants and higher rates of family formation in more conservative regions of the country. However, with the administration introducing tighter immigration restrictions and stepping up efforts to detain and deport undocumented workers, questions are emerging over whether there will be a sufficient supply of willing young workers to staff the growing number of factories being brought back onshore.

Another structural risk embedded in these demographic trends is the growing strain on Social Security and Medicare. These programs function as intergenerational compacts, in which today’s workers finance the retirement and rising healthcare costs of the elderly. Unlike 401(k) plans or IRAs, they are not savings vehicles but largely unfunded entitlements built on historical assumptions of higher birth rates and a broad, growing workforce.

As younger generations are increasingly less likely to marry, have children, or pursue stable, high-earning careers—instead relying more on gig-based employment—the system faces mounting pressure. These shifts raise serious concerns about the long-term sustainability of funding future benefits, particularly in a society producing fewer contributors to support the next generation of retirees.

Sources: Investing

Leave a comment