From US tariff policy and central bank meetings to the US government shutdown, developments that would once have moved markets significantly proved far less influential than in prior years. What does this shift mean going forward?

2025’s Biggest Surprise: The (Lack of) Market Impact from Economic Policy and Data

Key Points

- The biggest surprise of 2025 was how little impact economic data releases and policy decisions had on financial markets.

- From US tariff measures and central bank meetings to the US government shutdown, traditionally market-moving events failed to generate the reactions seen in previous years.

- Going into 2026, traders may need to treat official policy announcements and economic data with greater skepticism, while placing more emphasis on alternative and non-traditional data sources.

While 2025 was filled with dramatic price action across asset classes, the real surprise was what didn’t matter: economic data and policy decisions.

Even the US’s highest tariffs in a century—widely expected to trigger a recession—only caused a fleeting dip in the S&P 500. Markets quickly looked past the policy shock, reversing losses and pressing to fresh record highs long before the tariffs took effect.

Of course, a number of seemingly logical explanations have emerged in hindsight. The tariffs were ultimately not implemented to the full extent initially outlined for the world’s second-largest economy; companies rerouted supply chains through alternative shipping points; exemptions and carve-outs blunted their impact; and inventory cycles delayed the transmission of higher costs. Regardless of the rationale, the end result for traders who treated the policy shift as anything more than a brief, two-week disruption was clear: they overreacted.

This same pattern has repeated itself across a range of policy developments—from tax cuts and expanded fiscal spending to central bank rate decisions and even the longest government shutdown in US history.

A similar dynamic has also unfolded in the reaction to economic data. In the US in particular, and increasingly elsewhere, markets have rapidly dismissed “surprising” readings on inflation, employment, GDP, and sentiment that would historically have driven sustained moves.

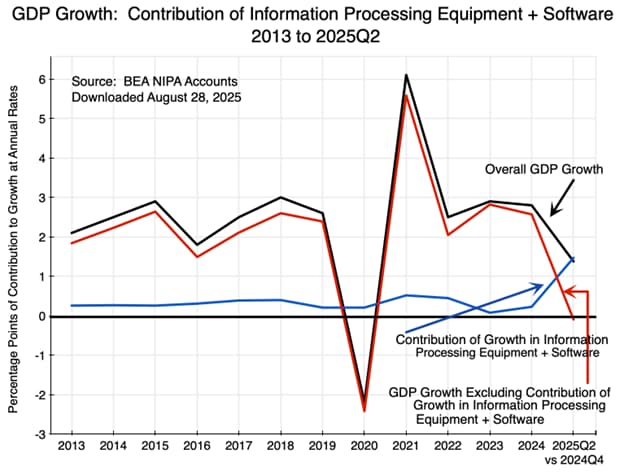

From my perspective, at least two forces help explain this shift. Chief among them is the dominance of the AI investment cycle and the associated wealth effect, which have diminished the relevance of traditional economic indicators. As long as AI hyperscalers continue to pour capital into data center expansion, broader measures of economic activity—and the data that track them—are likely to remain secondary considerations for markets.

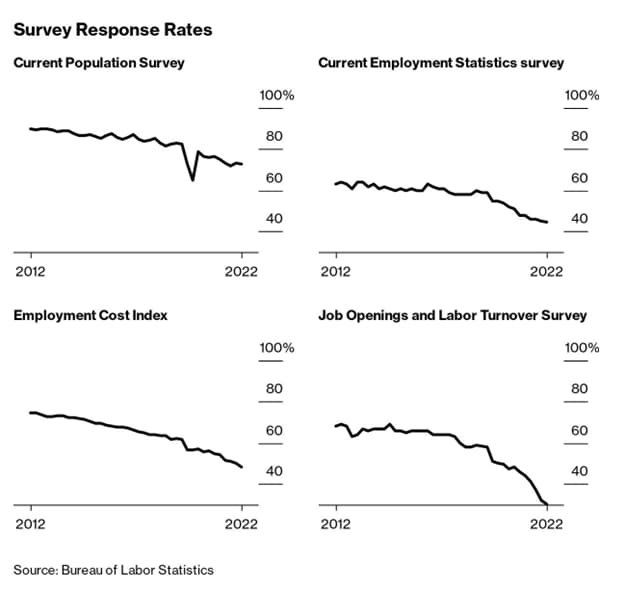

The second reason traders have largely discounted economic “surprises” is the growing perception that headline data no longer accurately reflects underlying economic conditions. For decades, much of the world’s economic data has been built on survey-based methodologies. In the post-COVID environment, however, response rates to these surveys have steadily declined, raising legitimate questions about their representativeness and reliability.

As participation has fallen, data volatility has increased, revisions have become larger and more frequent, and initial releases have lost much of their signaling power. In that context, it is hardly surprising that markets have become quicker to fade unexpected readings rather than treat them as durable signals of economic direction.

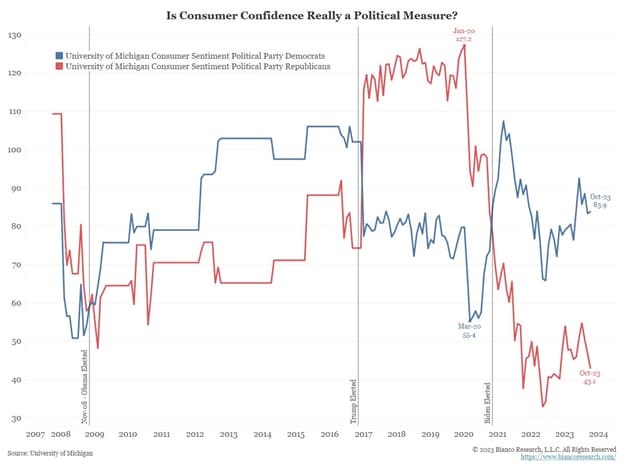

Tautologically, a survey with a shrinking respondent base is inherently less precise and less representative of underlying economic conditions. At the same time, the widening political divide has increasingly led consumers to assess the economy through partisan lenses rather than through objective evaluations of business conditions.

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment survey offers a clear example of this distortion. It has recorded sharp, election-driven swings in sentiment that appear to reflect views on the current occupant of the White House more than any meaningful change in economic fundamentals.

The good news—particularly for traders who focus on news and economic data—is that this surprise may not be permanent. Should the AI-driven investment cycle cool or political biases fade in the years ahead, traditional economic policy and data could rapidly regain their former influence over markets. Moreover, as demonstrated during the US government shutdown, alternative data sources can help bridge informational gaps and offer a more comprehensive view of economic conditions, even when official statistics are distorted by declining response rates or partisan bias.

The key takeaway for traders heading into 2026 is clear: treat official policy announcements and economic releases with a degree of skepticism, and increasingly supplement them with alternative data sources. Doing so may prove essential to navigating markets more effectively and improving trading outcomes in an environment where traditional signals no longer carry the same weight they once did.

Sources: Investing